A History Essay¶

My Horizons Essay on the History of Science, Technology and Innovation was nominated for the Arthur Acland Prize.

While I didn’t win, the process is what was important to me, and the process of writing the essay was a really fun one. Those who know me well know that I’ve got a particular interest in history; particularly, I find the works of Francis Fukuyama (The End of History), Benedict Anderson (Imagined Communities) and van Reybrouck (Revolusi) very interesting, and I was privileged (and am very grateful) to have teachers in secondary school who encouraged and nurtured my interest. In a world where I spend my time doing engineering, it was nice to go back to something that I did before and do it like I would have. Plus I didn’t know the prizes existed until I was told about them. This essay will be listed on the relevant Horizons module’s Blackboard page, and that means future years will be subject to the idiosyncrasies and curiosities of my mind and the pranks in this essay, which gives me a lot of joy.

Please find the essay below, excluding in-text citations that I have not included on the page. Many thanks to my Horizons tutor, Dr. Michael Weatherburn, for an engaging and thought-provoking module and constructive feedback along the way.

Did technology drive the creation of music in the 20th Century towards popularity or innovation?¶

Technological improvements, from the development of the phonograph to the invention of transistors, have reshaped the landscape of music throughout the 20th Century in terms of music composition and performance. For the purposes of this essay, popularity refers to contemporaneous popularity and is associated with ideas of homogeneity; innovation reflects contemporaneous innovation and is associated with an idea of diversity.

Alex Ross frames the development of music as a cyclical process – “First, the youth-rebellion period; [S]econd, the era of bourgeois pomp. Stage 3: artists rebel against the bourgeois image, echoing the classical modernist revolution. Stage 4: [T]he vanguard loses touch with the masses and becomes a self-contained avant-garde. Stage 5: a period of retrenchment. [Efforts of revival come] too late to restore the art to the popular mainstream.” This cycle forms the basis of this essay: the self-framing of musicians in the 20th Century and their music forms the basis of whether music was created with popular purposes or innovation in mind – with the disruptive influence of technology driving music creation largely innovative goals.

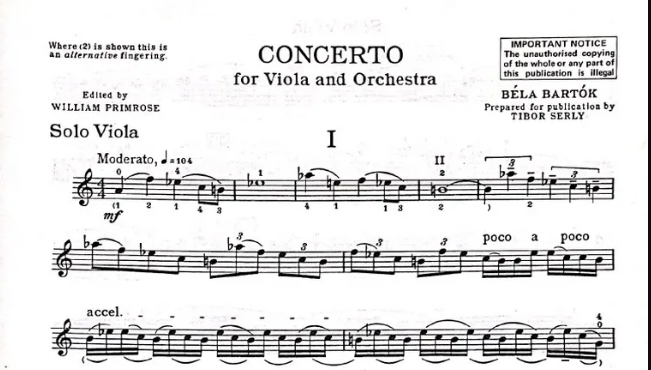

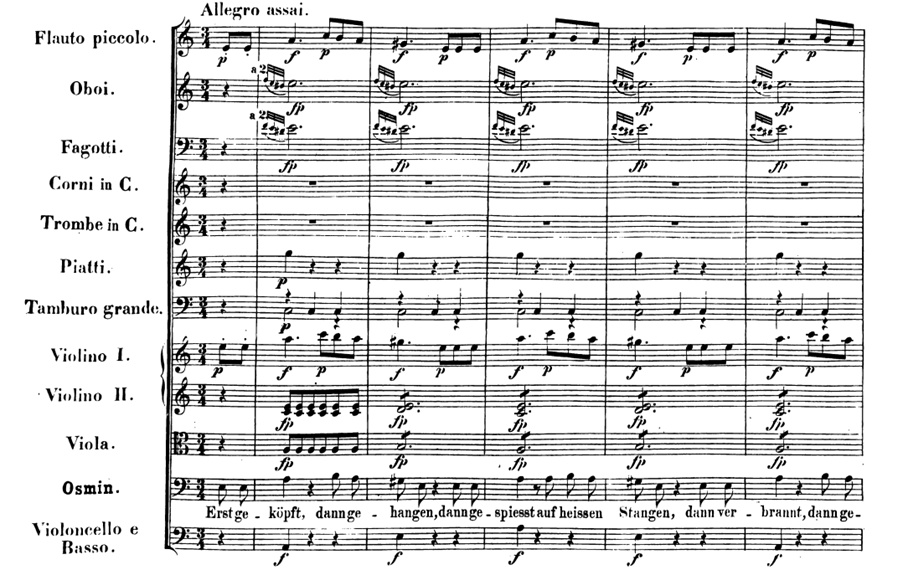

The invention of the phonograph and the ability to capture sound for the first time led to authentic folk music being captured for the first time. Hungarian composers Bela Bartok and Zoltan Kodaly recorded folk songs of peasants in the Transylvanian basin from the 1900s onwards; Bartok himself remarked that “It was decisively important for me to study all this peasant music because it showed me how to be completely independent of the universally prevailing major and minor scale system.” The effects of more authentic reproductions of folk music can be seen in the third movement of Bartok’s String Quartet 4, with the opening quasi improvisando cello solo reflective of tarogato melodies in Hungarian folk music, with Walker describing the melody as being “florid and full of chromatic embellishments”. Similarly, the opening of Bartok’s Viola Concerto centres around a scale not seen in the major/minor modes of classical music up till then. However, “Bartók was fond of this scale [A-B-C-D-Eflat-F-G-A] and […] it is a scale that appears in ancient folk music”. This was a marked contrast to the exoticism of pre-20th Century composers such as Mozart, who assigned musical characteristics based on perceived traits of an Other in Die Entfiihrung aus dem Serail. A commentary states that “[Mozart] plainly implies that Osmin’s eruptive rage is intimately related to the man’s being a Turk and thus […] “a foul-mouthed boor,” “insolent,” and an “archenemy of all foreigners.” Musically, it involves the addition of triangle, cymbals, and bass drum as instruments used by the Janissaries.

Figure 1: Bartok viola concerto opening. Note that only the 2nd note of bar 3 (E natural) is not within the folk music scale¶

Figure 2: Osmin’s aria (Mozart). Note the introduction of cymbals (Piatti) and Bass drum (Tamburo grande) as Osmin descends into rage¶

However, the widespread distribution of recorded sound through cassettes has also resulted in a reduction in diversity. In Indonesia, ethnomusicologist Anderson Sutton observed that “the former director of traditional gamelan music at the national radio station in Yogyakarta, Mujiono, often changed the way he had the radio station musicians perform the main melodic outline (balungan) based on new cassette releases”. Gamelan scholar Susan Whelan states that “when new gamelans are made nowadays they are often tuned to match a frequently recorded gamelan” , suggesting that the pressure of popular recordings has created an informal set of standards where there previously was a diversity of performance practice.

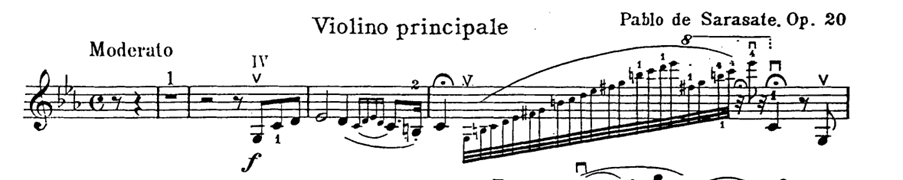

The effect of recordings on performance practice is not just one of popularity; a more primal concern, necessity, precipitated the usage of vibrato as part of violin performance practice today. Spohr commented that vibrato should “hardly be perceptible to the ear” , while Flesch describes it as a “thin-flowing quiver only on espressivo notes”. Katz argues that the advent of recording demanded a change in perceptions of vibrato, as a warm sound “helped accommodate the[..] limited receptivity of early recording equipment” and “offer[ed] a greater sense of the performer’s presence on record”. As a comparison, Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen as played by himself in 1904 utilises almost no vibrato in the opening passage, whereas the same piece played by Jascha Heifetz in 1937 uses expansive vibrato. The limited contemporaneous theory of acoustic recording horns meant that recording devices were suboptimal . A pulsed frequency through vibrato helped ensure that high frequency sounds were audible.

Figure 3: Opening of Zigeunerweisen¶

It was not just the effects of recordings that impacted the composition of music: technological developments in tangential art forms, such as film, drove music towards popularity at the cost of innovation. The development of film technology from stills, to silent cinema, to movies with sound created the genre of film music. Gorbman classifies film music as non-diegetic music, with a characteristic of “’Inaudibility’: Music is not meant to be heard consciously. As such it should subordinate itself to[…] the primary vehicles of the narrative.” Cooke states that “The orchestral music for […] features written by Hollywood film composers in the 1930s and 1940s was steeped in a late nineteenth-century romanticism that was several decades out of date in the concert hall.” This extended beyond Hollywood’s Golden Age: John Williams’ opening sequence for Star Wars was very much inspired by the opening to King’s Row , composed by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, a composer from the 1930s, who utilized filmic leitmotifs a la Wagner . Williams’s Star Wars scores relied on the tonality and rhetoric of high romanticism, which the composer recalled was a conscious move in order to give them not merely a ‘familiar emotional ring’ even when accompanying images of aliens but also to tap specific memories of shared nineteenth-century theatrical experiences . While it is not uncommon for composers to quote other composers , particularly in the 20th century, what stands out is the expressed conservativism of film music as a driver of popularity.

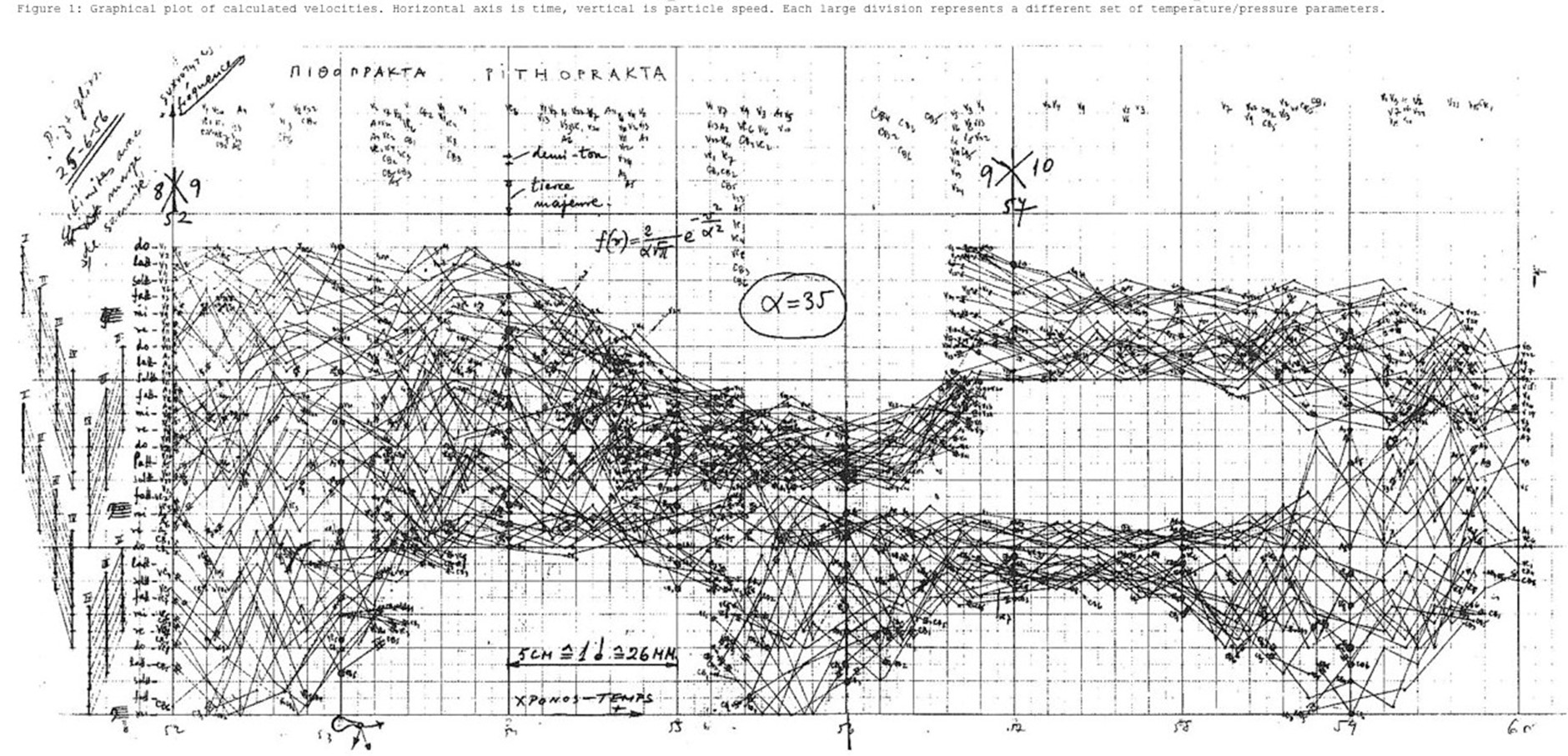

The 1960s and 1970s brought a paradigm shift: technology was perceived as an innovative source of music creation, particularly for avant-garde composers and in the rise of sampling. The idea of music as organized sound was particularly prevalent. Avant-garde composers such as Iannis Xenakis, a trained engineer and architect, utilised mathematical concepts in the form of stochastic processes and random motion in Pitoprakta – literally “actions through possibilities”. Pithoprakta’s goal was to distribute slopes (speeds) for each player such that the density of speeds is constant, with two slopes of the same length along the pitch axis averaging the same number of glissandi, and that the distribution of speeds is uniform – using a Gaussian distribution . Similarly, Karlheinz Stockhausen brought electronic devices into music through Mikrophonie , a series of compositions where “the microphone is used actively as a musical instrument, in contrast to its former passive function of reproducing sounds as faithfully as possible” . The unusual orchestration of microphone, tam-tams and band-pass filters mirrored the improved directivity of microphones, with ElectroVoice’s shotgun microphone being released in 1963 , and technological improvements in digital signal processing, with the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem describing the minimum sampling rate required to avoid aliasing of digital signals being published in the late 1940s , and paved the way for the spatialisation of sound , sampling, and the invention of electronic music instruments.

Figure 4: Pithoprakta score. Slopes are associated with pitches, with an upward slope denoting a sharper pitch.¶

Furthermore, the invention of the transistor and amplifiers precipitated the invention of electronic music instruments. This included standalone music instruments such as synthesisers and electronic adaptations of acoustic instruments such as the guitar and violin. This led to the number of musicians required to fill a hall decreasing: while larger audiences meant more volume was needed, the invention of the solid-body electric guitar and electric bass guitar by Fender and Paul “could fill the dance venues of the new urban environment without the need for the dozen or so […] players […] needed by the big band.” The big band itself was the precursor of this trend, with the invention of electronic microphones and moving coil loudspeakers in 1920 enabling the balance of string bass with big brass sections creating an alternative path for music creation to the 120-strong acoustic orchestra employed by Mahler and Strauss.

On the other hand, the improvement in digital signal processing (DSP) allowed sound to be sampled and edited in ways previously not possible. Together with the Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) control protocol, which contained information about pitch, strength of attack, decay, and timbre amongst other characteristics that could be captured, controlled and transmitted in real time . Blake states that “a [sampled] sound can be played back in real time, or transposed in pitch using any MIDI keyboard, or edited and reshaped […] or layered alongside other sounds to produce a more complex timbre”. The creation of sampling and sequencing machines, such as the Fairlight CMI and the LinnDrum as a drum machine allowed sampled sounds to be utilised throughout music for a low cost. The music produced through these means consisted of “repetitive beats and sampled voices” , with the Ibiza party scene serving as a catalyst for the mainstreaming of this style of music through the UK Acid House movement . Since then, sampled music has spread throughout different music genres and time periods, with 1996 R&B hit No Diggity being a sample of 1971 song Grandma’s Hands .

Figure 5: LinnDrum¶

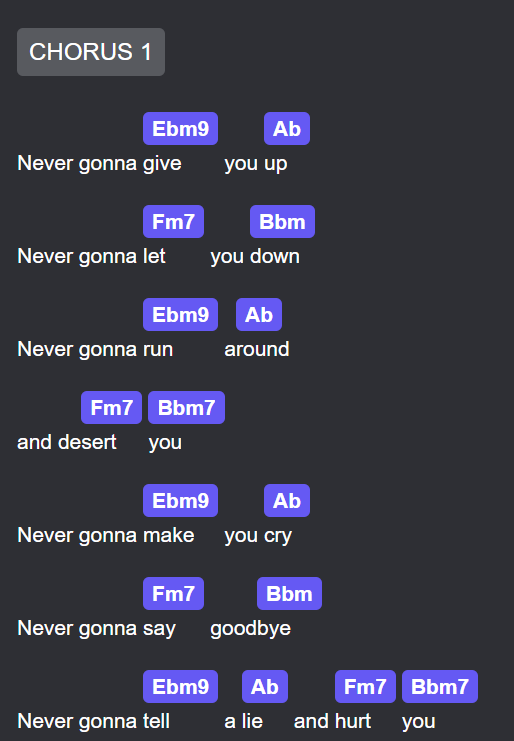

However, technology as a form of music creation through sampling negatively affected innovation inherent in the work. Brackett states that the conflict between analysing a piece of music by the “relationships which inhere in the work itself” as compared to the impact of a piece on the listener in pre-20th century classical music provide two possible foundations to analyse modern popular forms . Regardless of method, Brackett largely analyses the musical description on paradigmatic melodic features , which is revealing in what is not largely analysed: harmonic analysis and orchestration. The popularity of sampling with its pre-existing melodic and harmonic structures has led to homogeneity in chordal progressions across music, creating harmonically static ostinati such as the Royal Road progression , or the I-IV-V progression which is commonly used in Western art music with “the IV harmony as an intermediate step between structurally more important I and V harmonies”. The constraint of “harmonic stasis” forces innovation in other areas such as rhythm as in James Brown’s Super Bad . This has led to the rise of “four chord songs” as a reflection of the decreased harmonic innovation of pop songs.

Figure 6: Chords (from Yousician) for Never Gonna Give You Up with a ii7(Ebm9)-V(Ab)-iii(Fm7)-vi(Bbm) variation on the Royal Road progression(IV-V-iii-vi)¶

In conclusion, the relationship between technology, innovation and contemporaneous popularity is not a straightforward one; other factors, such as necessity, came into play, and innovation in one area might result in a decrease in innovation in another. Furthermore, it would be overly simplistic to assume even contemporaneous popularity as a static concept: Mahler believed that popularity and genius were incompatible, and an anecdote of Mahler being confounded by popular acceptance of Strauss’ opera Salome led him to question whether the voice of the people at the present moment or the voice of the people over time mattered more in Rosegger’s reply that Vox Populi, Vox Dei. However, the key factor underlying technology’s influence on music would be where a creator perceives their own placement, or their position in the collective social memory, within Alex Ross’ cycle. In some cases, such as the film music composers invoking a sense of nostalgia, innovation is not just sacrificed but pushed back upon to achieve popularity, while the reverse is true for avant-garde composers. Nonetheless, technology – in the form of recording, sampling and streaming, has created an irreversible shift, not just in music creation, but also in the historiographical context of accelerating Alex Ross’s historical cycles.

Listening Guide¶

HSTI Playlist, with timestamps of interest in square brackets:

Track 1: Bartok, String Quartet 4 movement 3 [8:50]

Track 2: Bartok, Viola Concerto [0:00-0:46]

Track 3: Mozart, Solche hergelaufne Laffen (Osmin’s aria) [4:41]

Track 4: Sarasate, Zigeunerweisen, played by Sarasate [0:00-0:20]

Track 5: Sarasate, Zigeunerweisen, played by Heifetz [0:00-0:23]

Track 6: Williams, Star Wars Main Theme

Track 7: Korngold, King’s Row Main Theme

Track 8: Bruch, Violin Concerto [10:52, theme in bassoons and horns]

Track 9: Strauss, Alpine Symphony [24:20, theme in horns passed to violins]

Track 10: Xenakis, Pithoprakta

Track 11: Stockhausen, Mikrophonie I

Track 12: Blackstreet, No Diggity [bassline and beats]

Track 13: Bill Withers, Grandma’s Hands [bassline and beats]

Track 14: James Brown, Super Bad

Track 15: David Bennett, Japan’s Favourite Chord Progression and why it works [0:00 chord progression, 0:42 Japanese examples, 2:38 examples in Western pop music]

Track 16: The Axis of Awesome, 4 Chords

Track 17: Rick Astley, Never Gonna Give You Up [chord progression]

References¶

Arnold, A. (1980) Once upon a galaxy: A journal of the making of the Empire Strikes Back. London: Sphere Books.

Arrow Electronics (2024) The Transistor Revolution: How Transistors changed the world Arrow.com. Available at: https://www.arrow.com/en/research-and-events/articles/the-transistor-revolution-how-transistors-changed-the-world (Accessed: 16 April 2025).

Blake, A. (2007) Popular Music: The age of multimedia. London: Middlesex University Press.

Brackett, D. (1995) Interpreting popular music. Cambridge University Press 1995.

Bribitzer-Stull, M. (2018) Understanding the leitmotif: From Wagner to hollywood film music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Byrd, C. (1997) ‘Star wars 20th anniversary: Interview with John Williams’ (1997), JOHN WILLIAMS Fan Network – JWFan.com. Available at: https://jwfan.com/?p=4553 (Accessed: 15 April 2025).

Cooke, M. (2020) A history of film music. Malmö: MTM.

DIYmicguy (2023) The history of the shotgun microphone, DIY microphones. Available at: https://diymics.com/history-of-the-shotgun-microphone/ (Accessed: 16 April 2025).

Forsyth, C. (1948) Orchestration. London: Macmillan.

Goldman, J. (2024) Avant-garde on record: Musical responses to Stereos. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gorbman, C. (1987) Unheard melodies: Narrative film music. London, Bloomington: BFI Publishing ; Indiana University Press.

Harkins, P. (no date) Journal on the Art of Record Production, Journal on the Art of Record Production “ Following the Instruments, Designers, and Users: The Case of the Fairlight CMI. Available at: https://www.arpjournal.com/asarpwp/following-the-instruments-designers-and-users-the-case-of-the-fairlight-cmi/ (Accessed: 15 April 2025).

The IEEE Signal Processing Society (1998) Fifty Years of Signal Processing: The IEEE Signal Processing Society and Its Technologies 1948-1988. Available at: https://signalprocessingsociety.org/uploads/history/history.pdf (Accessed: 16 April 2025).

Katz, M. (2010) Capturing sound: How technology has changed music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lai, E. (2004) Practical Digital Signal Processing. Burlington: Elsevier.

Locke, R.P. (2017) Music and the exotic from the Renaissance to mozart. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Maurice, D. (2008) Bartók’s Viola concerto: The remarkable story of his swansong. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online.

Nelson, D. (2012) Béla Bartók: The father of ethnomusicology. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=musicalofferings (Accessed: 15 April 2025).

Ramage, M. (2023) ‘The Royal Road Progression in japanese popular music’, Music Theory Spectrum, 45(2), pp. 238–256. doi:10.1093/mts/mtad008.

Roberts, G. (2012) Iannis Xenakis and his stochastic music. Available at: https://mathcs.holycross.edu/~groberts/Courses/Mont2/2012/Handouts/Lectures/Xenakis-web.pdf (Accessed: 15 April 2025).

Ross, A. (2007) The rest is noise: Listening to the twentieth century. New York, N.Y: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Ross, A. (2020) Listen to this.

Spohr, L. (1832) Violinschule. Wien: Tobias Haslinger.

Stockhausen, K. (1974) Mikrophonie I: Für Tamtam, 2 Mikrophone, 2 filter und regler, Nr. 15, 1964: 6 spieler. London: Universal Edition.

Stubbs, D. (2018) Future sounds: The story of electronic music from Stockhausen to Skrillex. London: Faber & Faber.

Sutton, R.A. (1985) Commercial cassette recordings of traditional music in java: Implications for performers and scholars. S.l: s.n.

Tedman, K. (1990) Edgard Varèse: Concepts of Organized sound. Boston Spa: British Library.

Thompson, D. (2021) I feel love: Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder, and how they reinvented music. Guilford, CT: Backbeat Books.

Venture, N. (2024) The lofi revolution: Unwinding to the sound of now. La Vergne: eBookit.com.

Walker, M.F. (1955) Thematic, formal, and tonal structure of the Bartok String Quartets. Bloomington, Ind, Ann Arbor, Mich.: publisher not identified, University Microfilms.

Warne, C. (2020) Acid house, Museum of Youth Culture. Available at: https://www.museumofyouthculture.com/acid-house/ (Accessed: 16 April 2025).